Advanced Overcomplication -OR- Compression Madness

So I realized in my last post that I opened a can of worms on all the wild and crazy variations of using compressors that get thrown around if you troll some of the many audio forums on the Net. This will hopefully serve as a basic explanation of some of a few of the different ways you can use compressors in mixing. I’m sure there are more than just these, but here’s a primer. Bear in mind, however, that if you haven’t mastered using a compressor to begin with, you should probably stay clear of anything beyond the Traditional compression. In fact, you can check out a post I did last year on learning how to use a compressor if you’re still fuzzy on the whole thing. Another thing to keep in mind is that most of these techniques come out of the studio; increasing the amount of compression you’re using in sound reinforcement can have the adverse effect of decreasing your gain before feedback if you’re not careful.

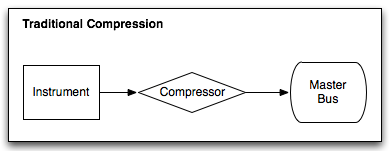

Traditional Compression

|

This is your standard method of using a compressor. You have a signal, it hits a compressor, and then it hits the master bus. Most commonly, the compressor would be inserted on an input channel. It might also be on an output buss or any other number of places in between. It could also be pre- or post-EQ in any of those locations. Regardless, this is sort of the tried-and-true method of implementing a compressor; one compressor doing the compression thing. This is the most basic use of a compressor and a skill that should be mastered before attempting any of this other stuff.

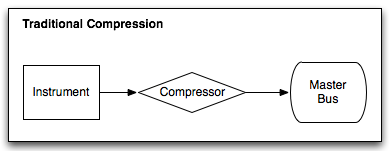

Parallel Compression

|

Parallel compression is a technique that developed out of recording studios in NY I believe in the 80’s. It’s sometimes referred to as NY Compression or Upwards Compression. The idea is you take a signal and split it or mult it so that you have it on two channels or busses. You compress one of the mult’s a bunch and the other one is either uncompressed or lightly compressed. Then you blend the two together. It’s called parallel compression because you have a signal with a compressor running parallel to your standard signal.

This is most commonly used on the drums where your parallel compression takes place on a drum bus. I’ve also heard of doing this on vocals and even bass. The result of this is tighter and punchier drums while retaining more of the original dynamics. It’s almost a texture or a color thing.

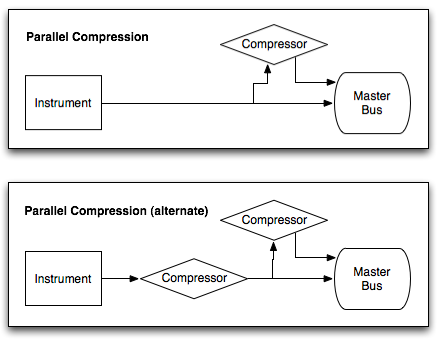

Serial Compression

|

Serial compression is pretty simple. It’s basically two or more compressors in a row. This is typically done so that you can run lower ratios to achieve more compression with less of the negative sound-effects of compression. Sometimes maybe you use a fast-ish attack/release on the first comp to tame the peaks and then use something a little smoother on the second one to level the whole thing a bit more.

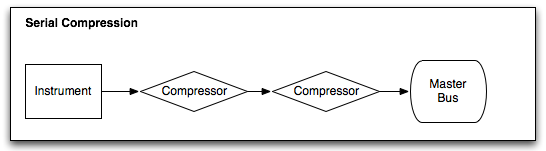

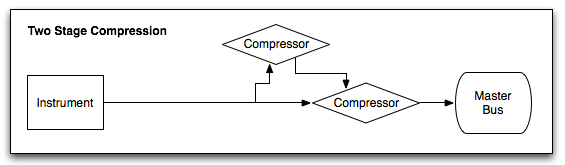

Two Stage Compression

|

Two Stage compression is something new to me. I guess Mike Caffrey did an article about it in TapeOp a couple years ago. He also has a couple of YouTube videos you can see here and here. In a nutshell, Two Stage Compression is sort of the next take on Parallel compression. You have your parallel compression happening and then you feed those channels/busses into a compressor. If you look at the diagram above, you’ll notice that the signal path is VERY similar to parallel compression, but the key is where you place that final compressor. I’m honestly not sure this method even bears mentioning since it’s really just an evolution of parallel compression, but if you dig around on forums you might hear about it. I have never experimented with this so I can’t really comment much on it directly.

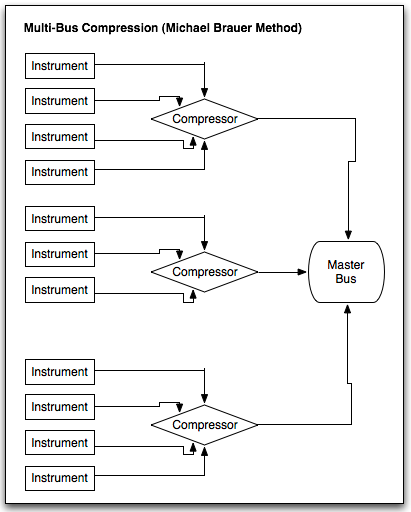

Multi-Bus Compression

|

Multi-bus compression is a method made famous by Michael Brauer(John Mayer, Coldplay). He developed this in response to some challenges he was having using a compressor on the 2-bus of his mixes. Instead of using one compressor for the entire mix, Brauer organizes his inputs into multiple busses(these days he typically uses 4) and uses a compressor on each bus best suited to those particular sounds. This way he is able to more appropriately color his instruments with the right compressor for the job.

Another thing to note is Brauer’s use of compressors is typically post-fade so that he is mixing into the compressor. This gives him a lot of flexibility to change the character and color of the compressor simply by changing a fader. A few weeks ago, Brauer twittered about how this technique helped him with a mix for the upcoming John Mayer record. You can find out more about this method at Brauer’s site.

Next up I will talk a little about how I’m employing some of these methods in my mixes.

Currently Reading:

Currently Listening to:

Previous Post

Previous Post Next Post

Next Post

Great post. I am a picture guy and this is exactly what I needed. Thank you. I have been doing the multi-bus compression without even realizing it too, I have a smack on the drums that I really just use occasionally (Really just to give the drums more pop when things get more dynamic on stage). but I am going to start using one on my vocals and my electric guitarists a little more now. Again thanks for the post!

Looking forward to the next part. Reading the last post made me think I should lighten up the compression on my parallel drum buss. I barely use any of that buss. It’s mostly because I start to lose clarity when I bring it in, and I don’t have long enough rehearsals to pay tons of attention to it. But what I really need to do is just loosen up the threshold, and possibly ratio, and do 6db or so, instead of crushing. I have been intending to do some buss compression with the vocals as well, but haven’t tried it yet.

A few questions…

1. What type of attack and release times are you using in the parallel vocal compression? I’m thinking of an attack around 8-10ms, which I think could help the intelligibility.

2. You mentioned getting some extra volume out of your vocals because of the parallel compression. Seems strange. How is it getting you more volume? You should be reducing your gain before feedback.

3. Have you done a post on master buss compression? I did a search and didn’t find anything. If not, would you consider doing one?

Josh, I’m glad you reminded me I was going to follow this up. I almost forgot.

You can lighten up the compression on the drum bus. It’s not the traditional implementation, but I know it worked a lot better for me. As far as your questions go:

1. I haven’t really settled on this one, yet. I’ve been playing with a fast attack and release which works sometimes, but then I’ve also been doing not quite so fast on the attack with a fast release. I guess I haven’t really landed on a start point, yet, but I think it’s going to be fast release with a fast-ish, but not super-fast attack.

2. You’ll get more volume when you use parallel compression for a couple reasons. For starters you’re summing the same signal together. If you take the exact same signal and feed it to a bus twice, you’ll get a 3 dB gain. Since compression raises your average volume level, you’re actually adding the same signal back in with a higher average level.

One of the results of raising your average volume level is you’re also raising your noise floor. Raising the noise floor will also raise the point of feedback depending on your room and setup.

I haven’t had a lot of problems with feedback when doing parallel compression on vocals lately, but things can get to the edge of feedback if I push the compressed side too hard.

3. I haven’t done a post on master bus compression because I don’t exactly compress the master bus. Now, I do run the Phoenix plugin on the Venue on my master music bus which is doing some compression, but outside of that I haven’t ever done any. On the studio side, I’m usually doing something to the music, but it’s maybe 1-2 dB. Probably fast-ish attack and slow-ish release.

The thing about master bus compression that has bitten me in the past is if you have something balance-wise out-of-whack in your mix, when that thing that’s out of balance kicks in it can potentially start knocking your entire mix level down and have it pumping in a not fun way. But a little bit on a well-balanced mix seems to kind of glue it together. Also, when I do use it in the studio, I start mixing with it in.

Yeah, master bus compression can be problematic live. I hadn’t done any for about 6 months. Then I decided to throw impact on during rehearsal, and I really got that extra pump, and a bit of glue on the mix. Some weeks it works, some it doesn’t. It depends a lot on the players for me. Especially when you are about 30 minutes into service, and all the players are starting to hit harder, with less sensitivity. The channel comps are kicking in more, and then the mast comp will kick in more. Pretty soon I am doing way too much compression.

It requires a lot of attention, but sometimes it adds some magic, for me at least.

I use a multi-band compressor on the master bus to give our live sound a polished, mastered feel. I’ve done that for at least 4-5 years now, and I’ve always found that it sounds better that way with our band than without. That may not be the case, though, depending on the band, the room, the system, and the amount of effects already being applied to each channel… Luckily for us, we have very good acoustics in the room and have everyone on in-ears, so nothing much that we do pushes us toward feedback. This allows us to go a little heavier on compression and also allows us to EQ mics so that they sound good (as opposed to EQing them so that they don’t feedback).