Guitars on Keyboards on Guitars on Keyboards

Am I the only one who struggles getting guitars and keyboards to play nice together with separation and distinction in a worship mix? There is some stuff I can do as an engineer at times, but in my experience when keys and guitars are fighting in a mix it’s most likely an arrangement issue. So today let’s look a little deeper at the musical side of what we do with audio and why there can be tension between these two instruments.

The first thing we need to understand is what happens when two instruments play the exact same note. Think about vocals. It’s very common to record a “double” or copy of a vocal performance in order to thicken it up in the studio. Dave Grohl’s vocals in a large portion of the Foo Fighters catalog are one example that comes to mind of a fairly strong double in the mix. The effect often sounds similar to a chorus effect, and if you ever wondered how the “chorus” effect got it’s name, now you know. The use of a double or triple is usually subtle in a mix, but at times it may also be more obvious.

No matter how it’s used, though, the double doesn’t typically have distinction in the mix. It’s support for the main take which is generally a bit louder otherwise the two just sorta smear together. So this brings up an important idea to understand:

If two instruments/voices are playing/singing the same note, the louder of the two is generally what our ear identifies while the softer of the two generally adds to the texture of the louder one. This is a really important concept to understand because what I have found in my years of mixing in churches is that quite often the keyboards and guitars are playing a lot of the same notes.

So why is that?

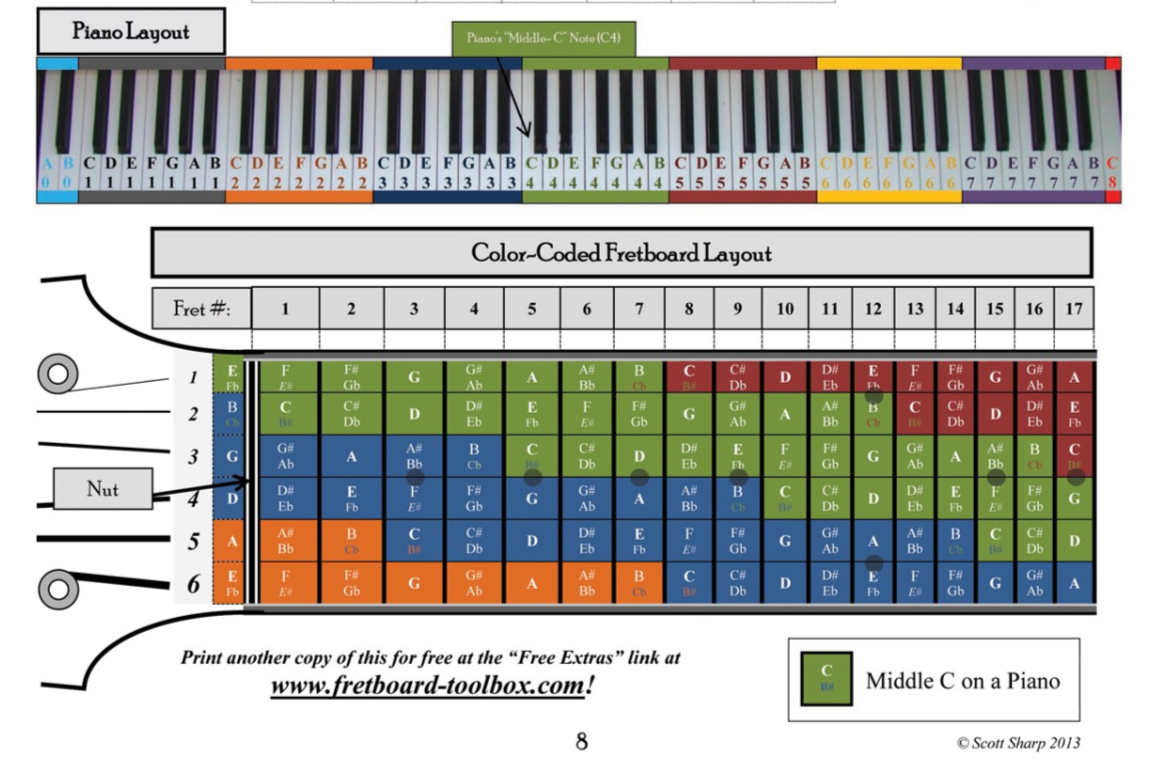

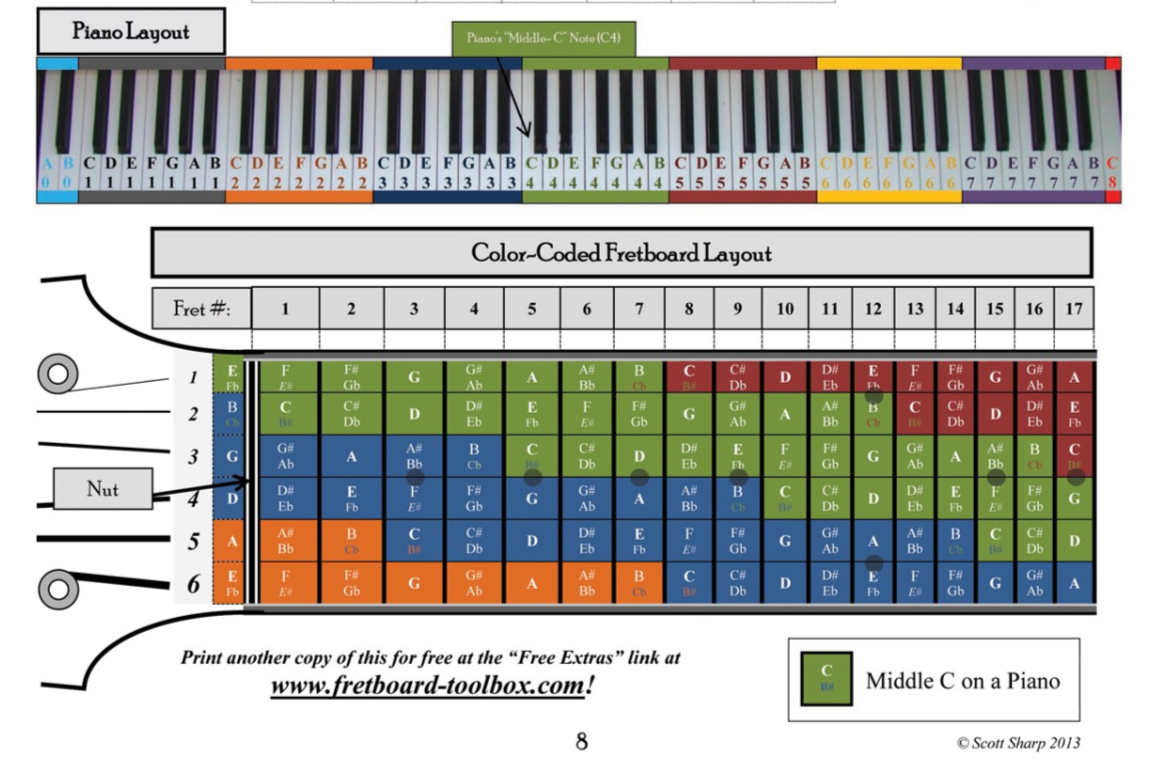

Let’s take a look at the notes on a guitar fretboard and a piano. The image below comes courtesy of Scott Sharp over at the Fretboard Toolbox. In this image, Scott has color-coded the notes on a piano and guitar to match so we can identify the same notes on each instrument.

www.fretboard-toolbox.com

When I took piano lessons as a kid, I was basically playing chords with my left hand and melodies with my right. This typically amounted to melodies getting played above middle C and chords played below middle C. On the diagram above, that means I would have been playing piano mostly in the octave colored in blue(chords) and the octave colored in green(melody).

So here’s a question for the non-musicians, if I play an open C chord on a guitar, can you guess which octaves that guitar chord will cover?

If you guessed green and blue, you nailed it. Of course, this really isn’t that hard to guess because the majority of notes on the guitar played by guitarists are in those green and blue octaves. What is worth understanding, though, is a typical guitar chord covers two octaves which is a little counter-intuitive since a chord is only three notes, but since a guitar has six strings and the average strummer is hitting 4-6 of those, we get most of those chords covering two octaves. Of course there are ways for guitarists to economize their playing, but not all of us do.

Since most keyboard players’ formal training doesn’t cover playing with a band, they also typically default to using both hands on the keyboard playing in those same two octaves around middle C. The sheet music I often see distributed to church musicians also points right to these octaves as well, and even if every musician in the worship band can read music notation–I hate to generalize, but most guitarists don’t, and I can say that because I am one–they usually ALL get the same charts.

So it shouldn’t really come as that much of a surprise when musicians in church environments are playing on top of each other especially if those musicians aren’t professionals. Most players aren’t really being set up to do anything else.

So how can we help with this as engineers?

I think the first thing to work on is learning to identify when band members are playing the same notes or in the same range. This is also for your benefit, by the way, so you’re not going out of your mind trying to figure out why you can only get one instrument or the other to work in the mix most of the time. Ideally you want to learn to do this by ear so if I think I’ve got overlapping parts I’ll often solo between them using solo-in-place or headphones. When you’re starting out with this, I think it helps to flip between the two sources quickly. You can also try humming each source to see if there’s a difference.

If you’re still having trouble identifying things by ear, start with what you can see. Take a look at that diagram above and compare it to your players on stage. Just don’t forget to orient it so it reflects your perspective in the house, though, as the higher octaves on the keyboard will be house left and a right handed guitar will have the headstock on the other side of his body.

If your players are actually playing the same notes at the same time, the next thing you need to figure out is if it’s an intentional musical choice. Sometimes it actually does sound great if everyone plays the same thing so I believe the best thing to do is have a conversation. Don’t do it over a talkback mic, though. Head down to the stage or find your MD and ask them what they’re going for.

When the goal isn’t to have everyone play the same thing and to get distinction between instruments, I typically suggest the keyboard try moving up an octave. Why the keys and not the guitar(s)?

Take a look at the diagram above again. The reality is the keys have a lot more flexibility to move out of the way as the majority of notes a guitar player will use are in two octaves especially considering most meat and potatoes guitar playing happens below the 12th fret. Now, one thing I should mention, though, is keys have been taking on more important roles in a lot of the modern worship music floating around over the last couple of years. If we’re working on a song where that’s the case, the keys need to take priority and the guitar(s) might benefit from moving.

Ultimately, if instrumentation is going to get rearranged, the music needs to drive things. For most of the stuff I do the guitars still get favored, but there are exceptions to that for some songs I encounter. I also know there are different styles of music within the worship genre that might favor something other than guitars so you have to approach things and make suggestions based on the context of what you’re doing.

If a conversation isn’t helping things, I will typically go with a couple of other options. First I’ll try and carve out dedicated space for each instrument in the frequency spectrum if I can. This is something I demonstrate all the time when I’m doing on-site training. The other thing I’ll do is simply make a judgement call on which instrument is more important based on my familiarity with the song.

At any rate, I hope some of this helps. The big takeaway I hope you get is that arrangement plays a big part in what will be heard in the mix. That doesn’t give us a pass from doing what we can as engineers, but, in my opinion, the arrangement is where you start in approaching this kind of thing.

A very interesting article: I’ve often found this type of ‘overlap’ between guitars (especially acoustic guitars) and keyboards playing in ‘piano’ mode. Slightly carving out different frequency areas for each instrument can certainly help. One point, though: most rhythm guitar players will mainly be playing BELOW the 12th fret (between the nut and the 12th fret), not above as you state. Small point, but it could confuse us guitarists who seldom stray up to the dusty end of the fingerboard! Keep up the good work!

Good catch, John. I fixed the typo.