Harsh Reality: Part 3 – The Wrong Tree

Now that my vacation is over, I’m going to try and catch up on some posts starting with this series.

First, let’s go back to a post in early July when I mentioned all the tuning and re-tuning we were doing to our rig. I mentioned I was having a love/hate relationship with the PA. Today I’m looking at some of those specific challenges we spent a few months working through.

As we’ve grown into the PA, a sort of running theme seemed to be that when we played back CD’s and listened to spoken word, everything sounded good if not great. I was actually pretty happy with spoken word from Day 1 because our far seats sounded so much better than anything I’d ever heard in the room, and we’ve improved it a bit at a time as we’ve worked on the rig. However, live music was a struggle pretty much from the start, and a very intense one at times. This wasn’t something I expected to happen when we installed our new world class rig especially when I’d already had success in other rooms on similar systems.

I just found myself having to do a lot of surgery especially on the mid’s and upward. Sibilance could be an outright nightmare. I started to feel like I understood why there are a lot of folks out there who tend to characterize Meyer boxes as being harsh; I honestly had always thought those gripes were more operator related, but now I was starting to wonder.

Now, don’t get me wrong. The PA still sounded good and mixes on it were improving as the weeks went on, but I think that’s to be expected on any rig; on a side note, it’s also why I don’t typically like going to opening night of a tour. Still, something didn’t seem right, and it didn’t seem like it should be so hard to get the mixes there. Having mixed in a variety of environments including the pristine confines of a studio, I was quite perplexed. In the midst of all this, I really started to question the whole linear PA thing for live music. After all, it seemed like the lower volume programming was good, but when we turned the rig up we were running into trouble.

It smelled like a perception issue to me, and I wondered if I should start shading the PA to deal with the challenges we were having. Part of my thinking was that this could also potentially help with mix translation. I theorized by shading the PA it would force us to make tonal decisions based on what we heard in the room that would work both in and out of our room. That line of thinking led me to study Equal Loudness a bit more and really look into some of the differences in our perception of sound at different volumes, and I have to say I actually walked away with a pretty good EQ compensation setting to counter the effects of Equal Loudness.

However, looking at it all now I’m pretty sure I was barking up the wrong tree. It happens to all of us.

The EQ compensation settings I came up with were definitely a win for me, but I’m convinced now that the system side of things was not the place for them. So what changed my mind?

Well, long-time readers probably know that my friend, Robert Scovill, has been a very large influence on my approach to tuning PA’s over the last few years. When he was in town a few weeks ago he was very gracious to give me some coaching while we looked at some stuff on the PA. In a very short amount of time he affirmed one of my fears; that we had been chasing our tails with EQ on the system. It’s an easy trap to fall into and looking back at the last four months it makes perfect sense to me how we ended up there.

It starts with a little tweak one week that seemed to work so you leave it on. Then the week after you need to tweak a bit more, but instead of first turning off what you did last week, you just add to it. Then you add some more and more and more and more. It’s misleading because the overall mixes seem to be better week to week, but the PA is slowly getting strangled.

So we peeled all the processing away to start with a clean slate, and after maybe 20 minutes of working on the main arrays everything sounded better. We had less EQ on the system than ever before, and the whole thing just seemed to open up. I hate the whole three dimensional description of sound that some folks like to use, but that might be another way to describe it. Most importantly for me, though, this was the first time the MICA’s were giving me the warm fuzzies I had previously only experienced from some other manufacturers’ rigs. And make no mistake, I live for line array warm fuzzies.

I mixed rehearsal that night, and that’s when the system really started to show its true colors. The MICA’s were really a breath of fresh air to mix on. It was just one of those mixing experiences that I didn’t want to end. I was really enjoying myself for the first time in a few months and remembering how I loved doing this mixing thing. My old vocal chains were finally working again, and if anything, I needed less processing than ever before. The rig still needed some little tweaks, but all-in-all it was meeting the expectations I had for it.

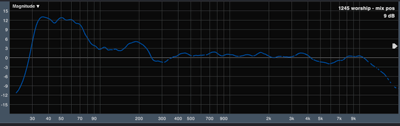

And of course the resultant transfer function we arrived at was essentially a linear transfer at the mix position (see accompanying photo). It might still get a little bit of tweaking in the 200 Hz range, but on a whole it plays so much nicer now. So, yeah, I just renewed my subscription to the Linear PA fanclub.

Now, I’ve still got at least one more chapter in this series of posts. Once the system is right, there’s still this whole translation issue. We still have a dynamics challenge to contend with; that didn’t magically go away when the rig got right. If anything, I think it may become more apparent.

Next up I’ll actually look at some of my own experiments–really, I will this time–along with some other little things I’ve set up to help with the dynamic and tonal challenges of getting an entire Sunday to translate outside the room. And I’ll also tease that most of these are things you probably don’t need a $50k+ console to do, either.

Previous Post

Previous Post Next Post

Next Post

Another thought is a sort of dynamic system EQ. I agree with you, that the Fletcher and Munsen curves at different volumes effect how we hear and judge from the speakers, so with that theory, why not write a program that when the PA was producing sound between 70-80dB it used an EQ preset that matched Fletcher and Munsen’s 70-80dB, and as the volume changes higher or lower it slowly and continuously changes in correspondence to the Fletcher and Munsen curves so that the system processing is continuously changing the EQ of the system (ever so slightly) as the volume of the music changes? Because I have heard some systems that sound great at 80dB, but awful at 100dB and awful at spoken word levels.

Equal loudness doesn’t really matter if we’re listening in the same room where the mix is happening. The mix engineer is going to make tonal decisions that he will perceive–in theory–the same as the listeners. He’ll either deliver or he won’t.

Equal loudness does come into play, though, when we try and transport a mix to a different environment and playback at a different volume than what the programming was originally mixed at.