Is It Really Doing What You Think?

I find it fascinating to study the engineering work of the big name mixing engineers. When I have time I watch and read just about anything I can get my hands on to see what nuggets I can glean. Then I like to take things back to my studio and sometimes into my “lab” to try things out and see what’s really happening. What’s interesting to me is I think some of these guys fall into the same kinds of traps the rest of us fall into where things aren’t doing exactly what we think they are.

For example, many studio mix engineers talk about how they will use an EQ on their mix buss. The most common reason I usually hear for guys doing this is so they don’t have to do as much work on individual channels. The typical approach usually involves a Pultec style EQ with a boost in the lows and a boost up top so they don’t have to carve the mids out of everything as much. But is that EQ actually doing this for them?

Thanks to things like artist endorsed plug-ins, artist presets, and some nice screen caps from mixing tutorials, I’ve been studying some of these settings for myself in my lab. I know my results aren’t exact replications of what some of these guys do because every piece of hardware is a little different, and I’m using plug-in emulations for my measurements. However, I believe replicating settings from a photo and using some of the presets often gets me close enough to measure what’s going on for those engineers when they are actually mixing. So let’s take a look at a couple examples.

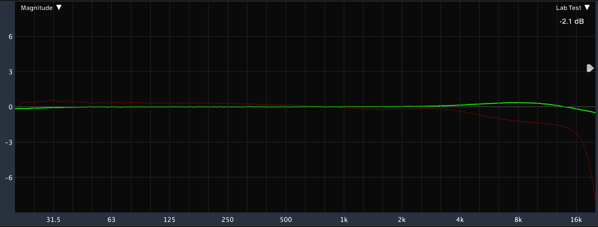

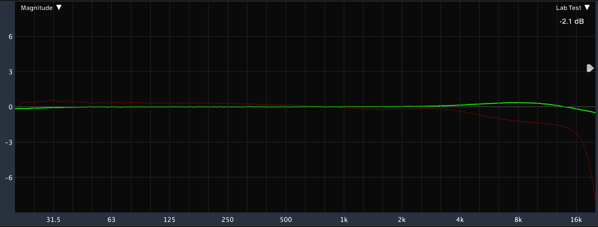

The photo above is a transfer function of a couple of Pultec settings used by a couple of A List engineers. I apologize that the red one is difficult to see against the green. Note that the scale on the left of the screenshot is dB.

Now, I’m guessing your first thought on seeing this is probably similar to mine: this is some fairly subtle processing. At most we’re seeing about 1.5 dB of change. So based on what you see here, how much do you think these settings would save you from cutting mid-range or doing any EQ for that matter? Let’s face it: these settings aren’t nearly as “smiley-faced” as the engineers who use them often credit them to be.

The thing about Pultec style EQ’s is they typically have extremely wide filters. They are so wide, in fact, that they can overlap which leads to the next thing you should take a look at.

In the upper-right of the image you can see “-2.1 dB”. That’s the offset on the green trace to get the bulk of the measurement back near 0 dB. There’s a similar offset on the red trace. I like to do this so I can see what’s actually going on in terms of boosts and cuts. In this case, the fact that there’s a -2 dB or offset means that the EQ settings are effectively boosting the overall level by a dB or two.

If you understand how “equal loudness” works, you may also understand that turning something up is the perceptual equivalent of putting a “smiley-face” on things because we perceive stuff to get a bit brighter and more low frequencies. Have I ever mentioned how deceiving audio can be?

So now you might be wondering what’s the point of what using this EQ like this? Have these engineers been drinking their own Kool-Aid? Have they fallen prey to mystical audio voodoo like the rest of us sometimes do?

Not necessarily.

Subtle adjustments on a master buss do make a larger difference than the same subtlety applied to an individual channel. I also wouldn’t doubt that to their sensitive ears, turning on this EQ gives the perception that they’re putting a little smile on the EQ. However, I think the plot is a little thicker than this measurement portrays.

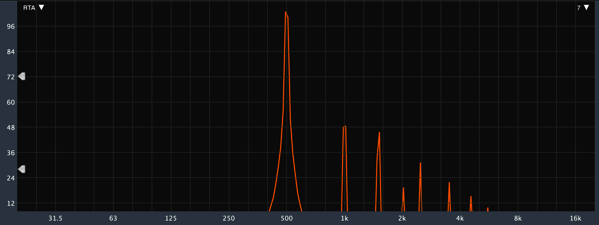

The photo above is of a 500 Hz sine wave passing through a plug-in emulation of a Pultec. The lowest spike you see is the original sine wave, and the spikes at higher frequencies are harmonics. The classic Pultec EQ’s are tube equalizers which means they add harmonic content. Most engineers would affectionately refer to this as color. So it’s not just a little bit of EQ that these engineers are getting out of using the EQ. They’re also getting color.

But why does this matter? Who cares what’s really going on? Can’t we just turn knobs and have fun?

I’m paraphrasing, but one of the many things I learned while working under Andy Stanley was if you don’t understand how something works, you won’t know how to fix it when it’s broken.

In the case of mixing, if we don’t know how we are actually getting a sound, when we are faced with a new environment or a new set of tools, we won’t know how to make things work. For those of us who travel around to different venues, it’s nothing new to be faced with a different set of equipment on a nearly daily basis. However, even if you are mixing in the same place all the time, this can still get you because things break and stop working or even get upgraded. Nothing is permanent.

Another reason this is important is because when you are learning from someone else, you still need to try and test what they’re doing for yourself. Nobody gets everything right, and sometimes what we think is going on isn’t what’s really going on. Take the EQ example above. The bigger impact many engineers get from using a Pultec on their entire mix might be the color of the EQ and not the EQ itself, but if you listened to those engineers talk about the EQ and then tried to use a different EQ, you wouldn’t get the same results. You might even get discouraged after trying things and not achieving the intended results. But the problem might not be you. The problem might be in the explanation you were given.

So when you’re learning new stuff, don’t be afraid to tear things apart and figure out what’s really going on. At a minimum it will give you a better understanding of what’s actually happening, and in the process you will likely become a better engineer as well.

Previous Post

Previous Post Next Post

Next Post