Learn Your Scales

It’s no secret I’m a big fan of using measurement software. It’s one of the many tools I love to employ for all things audio whether it’s optimizing PA’s or mixing. I even use it in the studio these days. I’ve just found it to be a great tool to confirm what I’m hearing when things are out of whack. But I’m still always ears first, eyes second.

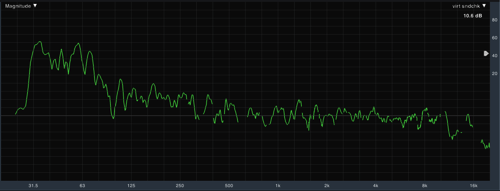

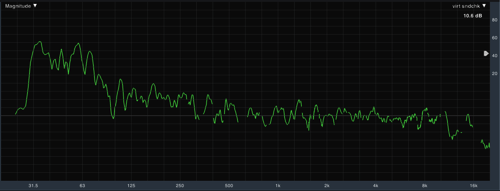

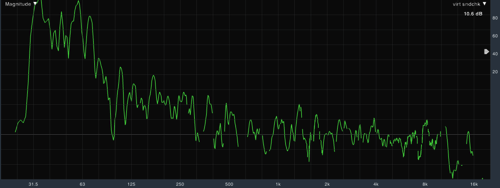

So today I want to address something I think folks who are newer to using measurements sometimes trip up on regardless of the measurement platform they use. Take a look at the following two screenshots of a couple transfer functions from Smaart. These both have a resolution of 1/24 of an octave and were screen captured in a double-pane view.

So what’s the difference between these two measurements? Which one looks better?

Take a look again.

Did you figure it out? Maybe you figured it out the first time I displayed them.

If you aren’t seeing it, yet, you should know that they’re the exact same measurement. The only difference is the vertical scale which you can see on the left of the captures in the second set.

You can make just about anything measure well if you zoom out far enough. In this case, the vertical dB scale in the first capture is compressed relative to the second capture. The scale in the first is what my version of Smaart defaults to. The second scale is set to approximate what I usually see Meyer Sound’s SIM 3 default to.

So what’s my point?

If you’re going to use measurement software, you have to understand the resolution of the measurements you’re making. You have to understand the scale. Things can “look” very different to you if the scale isn’t what you’re used to, and this can influence your ability or inability to make decisions using the information. For example, as I mentioned I often use measurements to confirm things I’m hearing so if I were to just glance at a measurement and see something I’m not expecting, it could potentially send me down a rabbit trail of troubleshooting.

So what scale do I use? It depends. There are times I like it compressed, and then there are times I like to zoom in on things. It depends what I’m doing, although, I will say that I think sometimes when the scale is zoomed in too far I see guys start nickel and diming things.

If you’re looking at the second measurement with the scale zoomed in, it can be very easy to get carried away chasing all of those peaks and nulls. But those peaks aren’t really as bad as they seem especially if you could see the coherency of the measurement because these were taken with the entire system on, and the mic not in the optimal spot I would use if I were optimizing the system. Yet, I’ve seen system techs go after things like that with a ton of little narrow filters, but if I move the mic a few feet one way or the other that stuff will likely all shift.

This is why using a more zoomed out scale like in the first measurement can be helpful at times. With things zoomed out it can be easier, in my opinion, to spot the trends that could be issues and then attack them with a couple of broader filters instead of many narrow ones.

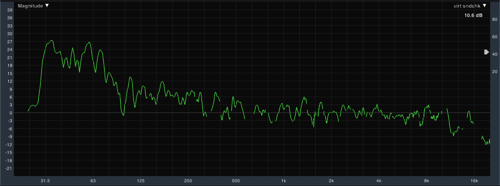

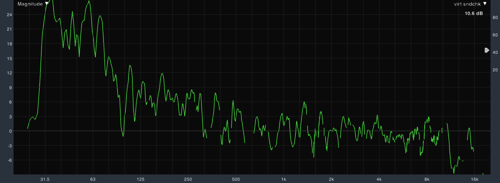

The RTA I use is another example of a scale that is zoomed out. You can see an example of this below.

This is where my version of Smaart defaults in a double-pane display, and I like it. With the scale zoomed out, I can more easily see the average response of sound in the room. I’m not going to be cheating to find frequencies that feedback with this view or doing surgical EQ with data from this, but it has proven useful to me in achieving a more consistent sonic signature from week to week which is what I’m really using it for in the first place.

And this leads to my last point.

If you’re going to use measurement software or hardware, you need to know why you’re using it in the first place. I believe this can be said for any audio tool whether it’s gain, EQ, a certain mic, dynamics, processing, etc. etc. etc.

I configure my measurement software a specific way to give me the measurement feedback I find most useful, but that doesn’t mean the way I use it would be useful for you. You have to figure out what you are trying to get out of your tools, and then use them appropriately. This might take time to experiment, dig through different options, and maybe just maybe even pull out a manual. Remember, you have to learn your scales if you want to play your instruments.

Previous Post

Previous Post Next Post

Next Post