No Prescription

I was thinking of this the other morning in regards to the clarity of sounds kind of piggy-backing off an article I wrote not too long ago. Some of this is sort of sound fundamental stuff so some of you might just skim this one. Also, be warned I’m going to simplify some things here because you don’t need a physics degree to mix.

The sounds we hear are made up of multiple frequencies. First we have the fundamental frequency which is the lowest frequency of a sound. In musical terms, this frequency is the note being played by the instrument. There are charts floating around that show different instruments’ frequencies, and the frequencies shown are typically the range of fundamental frequencies the instrument can reproduce.

Of course, this is only one part of the sounds we hear because in addition to the fundamental frequency are an array of overtones. Overtones are basically any frequency content of a sound that is higher than the fundamental. These include harmonics of that fundamental frequency but also include in-harmonic content as well. The relationship of all these frequencies together is what gives an instrument its timbre and is part of how we identify something as a voice or a drum or a piano, guitar, flugelhorn, etc. The whole idea of synthesizers was to synthesize sounds by taking a frequency and adding overtones to it to create a sound. Of course, there’s more to sound than just frequencies, but that’s something for another time.

So, the fundamental frequency is, well, fundamental to the sound so that usually needs to be heard for something to be clear. The challenge, though, is clarity of the instruments in our mixes is really derived from the harmonic content.

Let’s take a kick drum, for example. An average kick drum’s fundamental is usually around 50-60 Hz. The 2nd harmonic around 100 Hz is usually also important and often helps define that chest punch some of us enjoy; strangely, though it’s the fundamental that technically has more of the “feel”, but that’s a topic for exploration on another day.

Now, if the kick’s fundamental and 2nd harmonic were all you could hear from that kick drum, you likely wouldn’t recognize it as a kick in a mix. Sub-low frequencies alone just don’t give our ears enough information. You’d know this if you ever muted your mains and only listened to your subs, but even if you haven’t, you’ve probably experienced this at a traffic light when someone pulled up next to you with their subs crankin’. The punchiest low-end is often rendered as mush when you push it only through a subwoofer; the definition we sometimes hear with only subs going is often a result of distortion happening with the speaker. To get definition, or clarity, in a kick drum we need some snap around 1kHz and/or point/click around 5kHz. It’s these upper frequencies that give us clarity and definition.

Electric bass guitars are similar. We have fundamentals from probably 40Hz up into the low-mids in the 300Hz range, but we gain clarity in the mid-range often in the 700-1k range. Sometimes a little bump even higher than that can help as well. When we move into things like vocals and guitars and keyboards things get even more complicated.

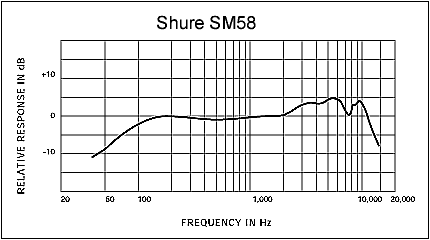

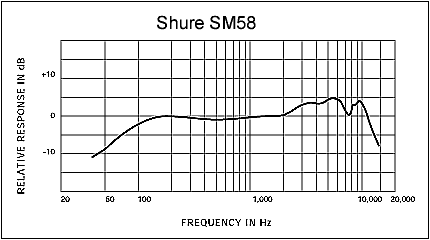

Regardless of what the instrument is, though, I’ve found that getting complex sounds to speak in a mix requires emphasis of a couple of frequency zones: the fundamental frequency and the harmonics. Now, by emphasis I don’t necessarily mean boosting those areas. They can be naturally emphasized as well. For example, take a look at the frequency response of a Shure SM58.

A lot of people bag on SM58’s, but there’s a reason why they’ve been ubiquitous vocal mics for decades. The proximity effect(not shown here) bumps the fundamental, and then there’s a rise in frequency response in the upper-mids.

Of course, emphasizing these areas alone doesn’t give you clarity. A proper frequency balance is still required for things to sit right and sound natural. Sometimes that means doing things that aren’t necessarily intuitive. For example, I often high-pass electric guitars above 100Hz sometimes going as high as 150Hz. If the fundamental frequency of the lowest note in a guitar with standard tuning is 80Hz, why would I do this?

I do it because sometimes the low end is unnaturally accentuated due to mic placement, poor in-ear reference for the player, and any number of other things in between. Remember, a high-pass filter is not a sheer cutoff in frequency; it’s a low frequency roll-off. So by raising my HPF’s frequency, I’m attenuating things below that frequency often in a smooth fashion to get the guitar’s fundamental in balance with the rest of its tone while also allowing room for the bass guitar to live.

Not every engineer does this, though. Joe Barresi is known to not roll anything off. Of course, he’s also probably getting tracks either he has recorded himself or that have already been cleaned and balanced. So my point is, there’s no prescription for this stuff.

Now this is all fine and good for individual sounds, but we’re not delivering individual sounds. We’re putting up a mix, and that means all these individual things need to live together. If you’re thinking through what I’ve already talked about, you’re probably starting to understand that stuff overlaps. I mean, how can it not? If a bass guitar is really just an electric guitar with the lowest note one octave below, there’s a lot of room for overlap between those two instruments. I’m not even going to get into keyboards…

When things overlap at the same time, or in other words, play the same notes, we run into the risk of masking. In simple terms, masking is when one sound covers another. Typically it’s the louder one that wins.

Great arrangements go a long way towards preventing masking, but even a great arrangement can run into issues. This is why engineers talk about making space for things. One of the ways I get separation and clarity is by giving instruments their own real estate in the frequency landscape, and once again there’s no clear cut prescription for this sort of thing. If you dig around on the internet you can get some ideas, but I’ve found what works can really be case-by-case from band to band. For example, in a keyboard heavy band I’m going to handle the keyboards differently than I’d handle them in a guitar driven band. As I mentioned in my earlier article on clarity, I believe the music needs to drive this kind of thing.

So you can roll all this stuff around in the back of your mind and know that there are solutions to be found for many of the challenges we face. Ultimately, though, you’re gonna have to turn the knobs yourself and figure out what works. There are some guides, suggestions, and ideas floating around the net you can draw from. Some of these are good, and a lot of them are bad so you’re going to have to figure out what works for yourself. I do have some strategies for teaching yourself to figure this out, but I’m going to save that for another time. In the meantime, turn the knobs and see what you can come up with.

Next Post

Next Post