The Double-Edged High-Pass Filter

High-pass filters–also known as low cut filters–are a pretty simple thing. They filter out or attenuate the sound below the frequency they are set at. A big mistake new engineers make is to not take advantage of these simple tools, however, some engineers often get too heavy-handed with them.

So let’s back up. Why would you want to use a high-pass filter in the first place?

*** Audio 101 ***

The primary reason is basic clean-up. Microphones tend to capture a lot more information than we actually need and not all of that information correlates with what we’re actually capturing. A big case-in-point is low frequency energy. This can be from mic handling, vibrations from the floor, trucks going by outside, HVAC, etc, etc. On one input this noise might not be audible on all playback systems or PA’s, but across multiple microphones it tends to add up and cloud the mix.

*** End Audio 101 ***

High-pass filters are also employed by engineers to help make space in the mix. For example, consider a keyboard and a bass guitar. Keyboards are typically full-range instruments that can cover the entire frequency spectrum while the bass guitar tends to live in, or at least dominate, the lower end of the spectrum. Not all keyboard players understand they don’t necessarily need to play down low when a bass guitar is covering those notes so a high-pass filter can be helpful at times to keep the keyboard from stepping on the bass guitar.

The thing about doing this kind of thing is it shouldn’t be an automatic move. It’s a case-by-case technique especially in live sound. You might be concerned about that keyboard player during a full band tune, but what happens when that keyboard is the only instrument padding? Or during a solo piano tune? That low frequency information might be nice in there.

This is the double-edge nature of a high pass filter. On the one hand it can help a lot in cleaning up a mix, but when it’s just applied without listening to everything it can bite you.

Here’s an example I’ve seen a lot over the last few years in multiple churches. It’s not unusual for me to look at someone’s console and find high-pass filters on vocal mics set to 250 Hz and even higher. How this happens is perplexing to me. Take a look at the image below.

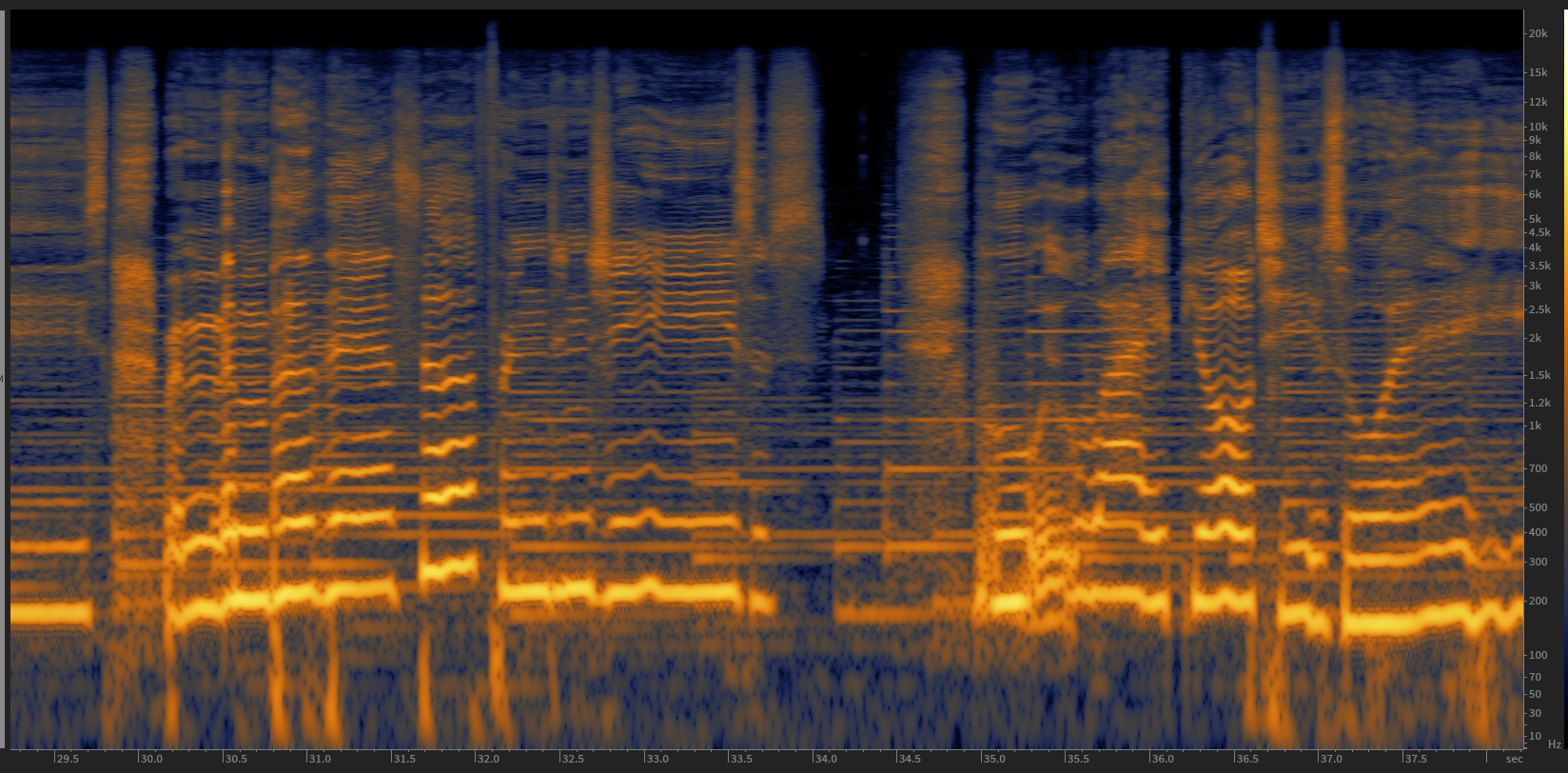

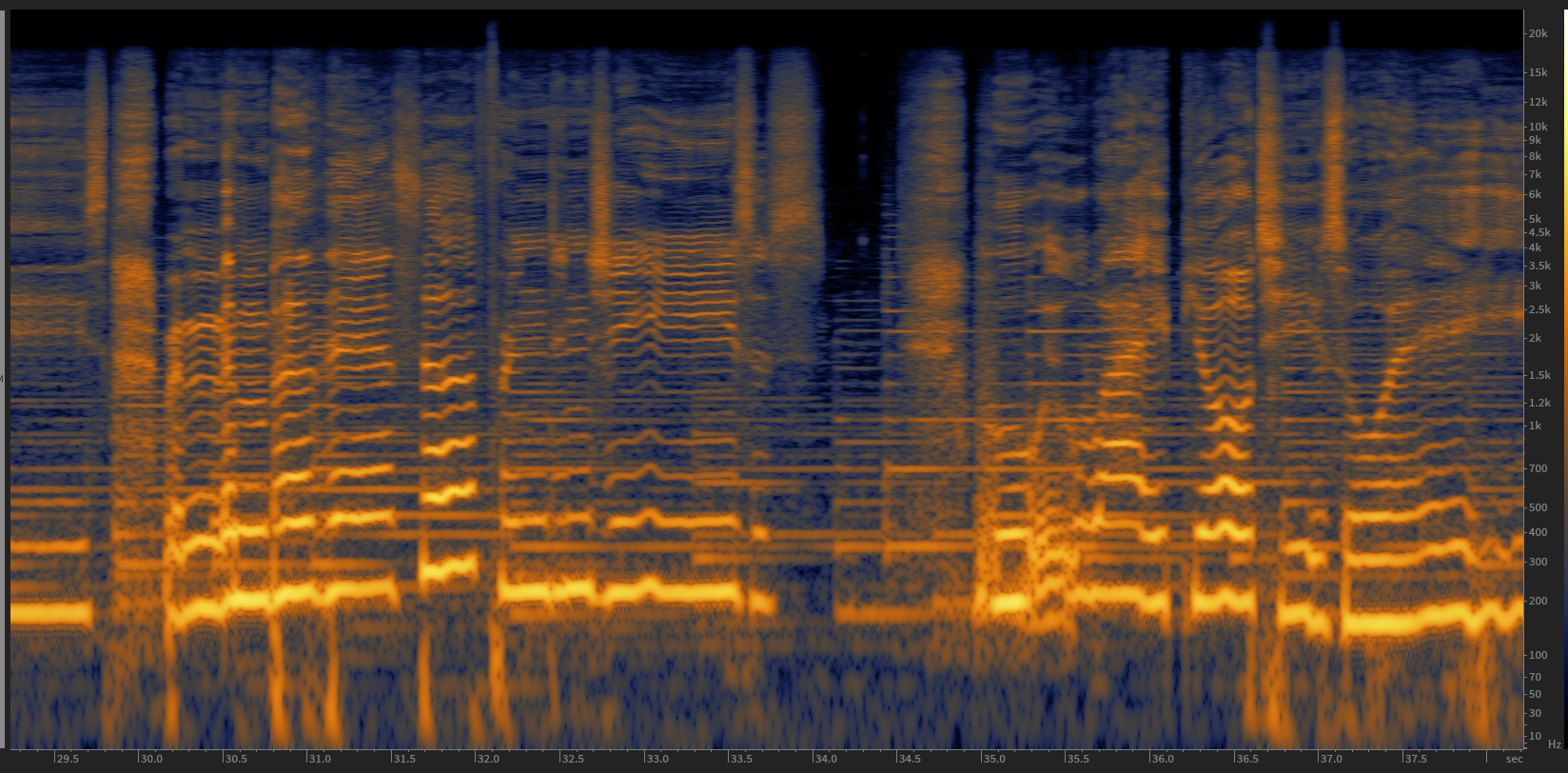

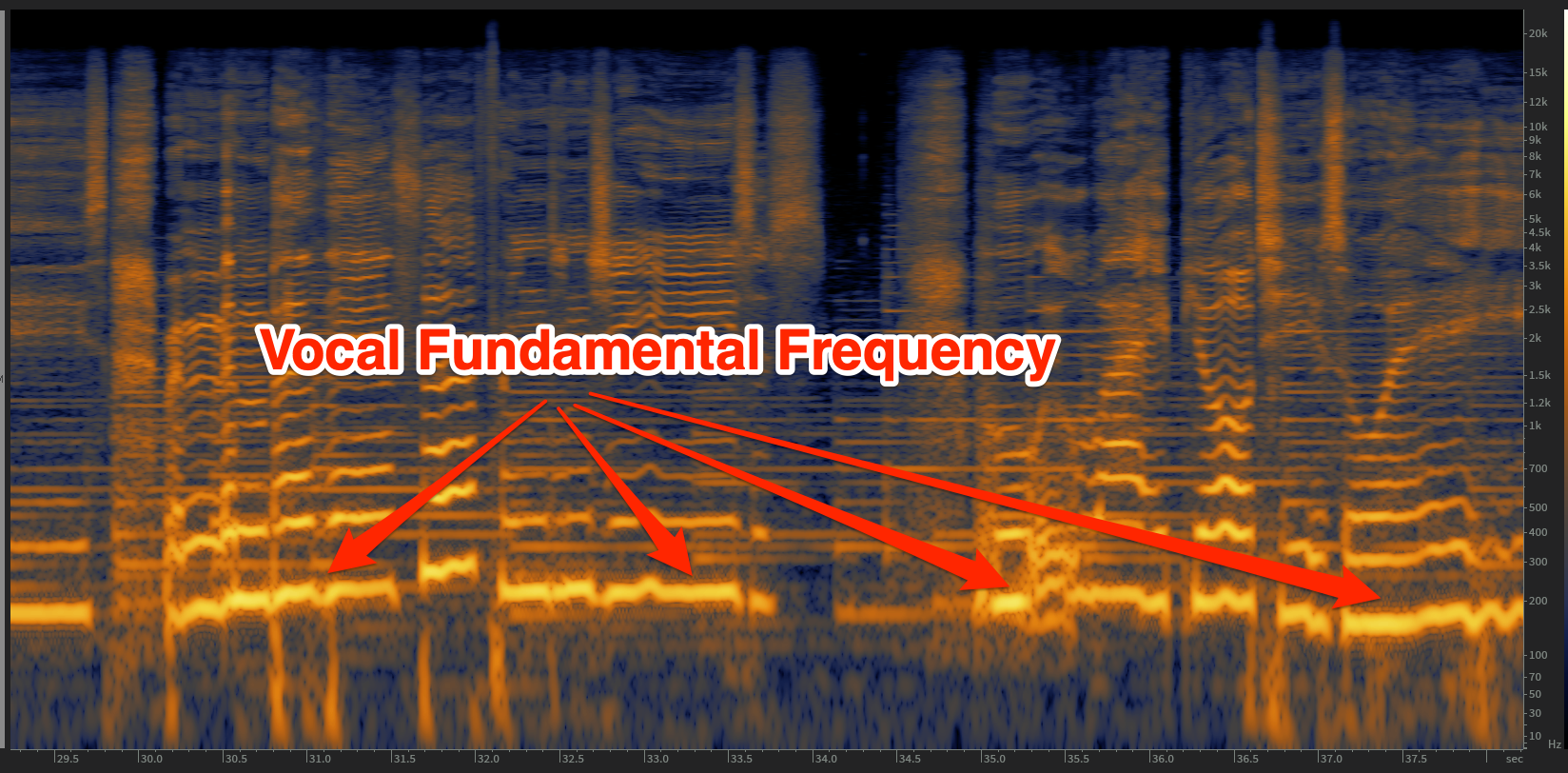

I snapped this while I was doing some clean up work on a male vocal in Izotope RX. What we are looking at is a spectrogram which displays frequency energy over time of the recorded vocal. The brighter–or more intense–colors indicate more energy. Take a look at the lowest frequency that stands out.

These lines represent the fundamental frequency of the voice. The parallel lines above the fundamental represent the harmonics of the voice. You probably noticed that none of these lines are static because this is a capture of singing, and that fundamental frequency represents the NOTE that is being sung. It’s the frequency that defines the note and really the voice itself which is why it’s called the Fundamental.

The information you see below that fundamental represents uncorrelated sound. It might be background rumble or noise or bleed from other stuff on the stage. Some of the noise is vocal plosives that I was in the process of cleaning up when I took grabbed this image. The bottomline, though, is this stuff isn’t good vocal stuff. It probably doesn’t need to be there and is ripe for targeting with a high-pass filter.

Where should the high-pass filter be set at, though? Let’s take a closer look.

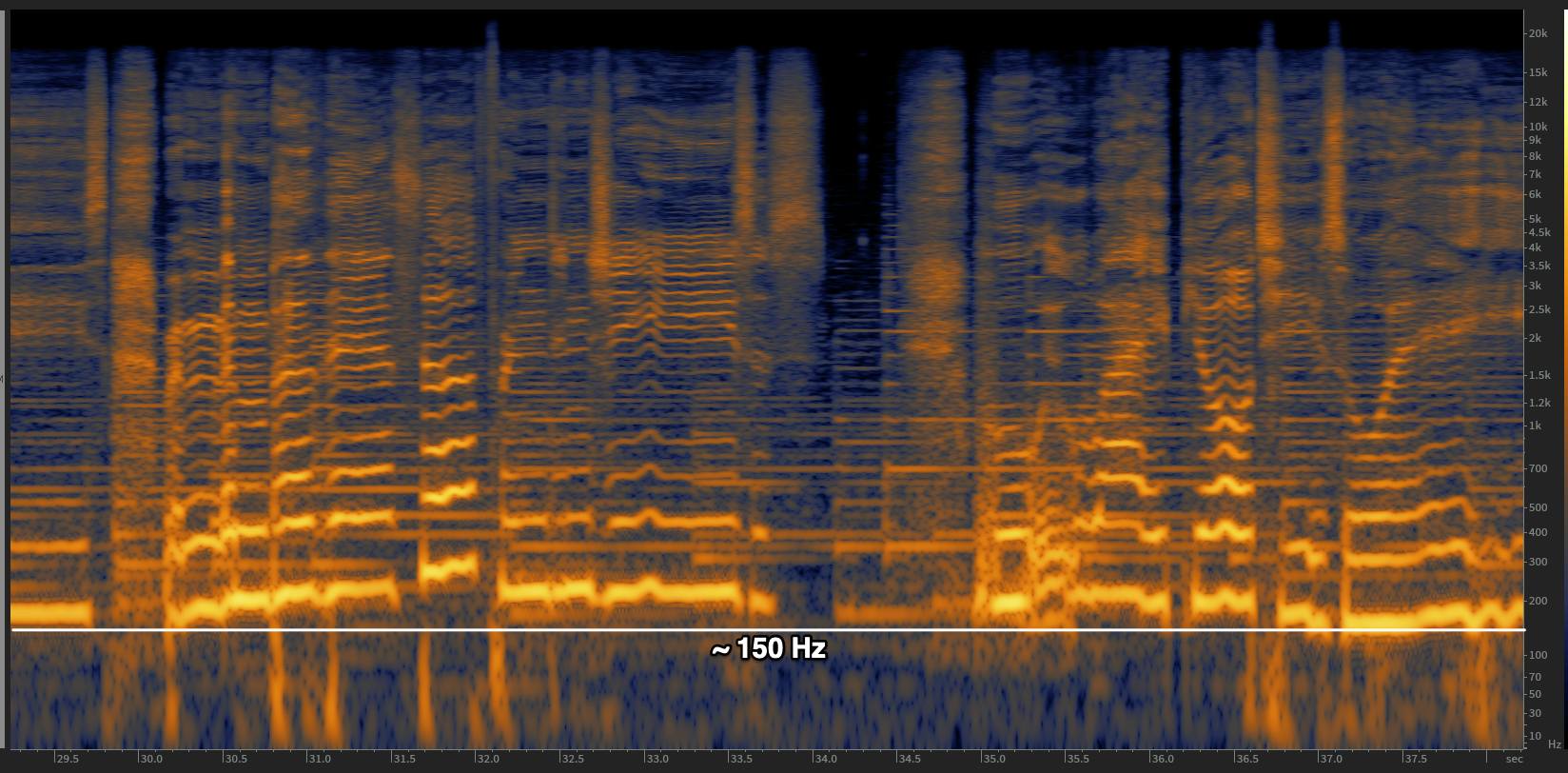

I’ve added a white line to mark approximately where 150 Hz is. Notice that the fundamental is still dipping a bit below 150. That means if I ran a high-pass filter on this vocal at 150 Hz, I would start removing part of the actual vocal.

Now, on the one hand, maybe taking a little of that out might be OK sonically. Maybe there’s a lot of proximity effect and going a little higher would help tame that. That’s not always the case.

Something else to consider is this particular vocal was a tenor. That means other vocals will go even lower than this so a high pass filter even set to 150 Hz on a vocal is going to be too high for some vocals which is why I am often confused when I find a high-pass filter set at 250 Hz or higher on a vocal.

But high pass filters aren’t brick wall filters, they….

Let me stop you right there. It’s true that high-pass filters aren’t brick wall filters, and they roll off at a particular rate such as 12 dB per octave or 18 dB per octave. So let’s translate that to the 250 Hz filters I find on a lot of vocals.

A lot of console filters are 18 dB per octave filters. One octave below 250 Hz is half the frequency(125 Hz). That means a HPF at 250 Hz will cut ~18 dB at 125Hz which means in this example we’ll have somewhere around 12-15 dB of cut on that fundamental frequency. While it’s not unusual for me to remove some proximity effect from live vocal mics, that’s very extreme for me.

So how do I set a high pass filter?

In general, I start low and adjust it higher until I hear it affect the sound. Then I back it down a bit so it’s not audibly changing my source. Once I know what the highest point is I can take the filter to without adversely affecting the sound, I’ll make a determination on whether I want to go higher based on what else is happening in the mix. In the vast majority of cases where I’m just cleaning up low frequency muck, I won’t go higher.

For example, let’s say I do have a vocal with excessive proximity effect. I could raise the high pass filter a bit to try and balance the tone of the vocal a bit, but what happens when that vocalist pulls back off the mic? Now that fundamental is going to be hacked away because high-pass filters are sharp tools.

Personally, I prefer to address that sort of thing with a bell filter or shelf. I feel like this gives me much more control and precision. Plus, I can split the difference more easily this way if I need to. A dynamic EQ like the Waves F6 can be even more powerful for addressing that kind of challenge.

Now let me sum this all up.

High pass filters can be powerful tools, and that’s a blessing and a curse. Should you be using them? Probably. But you should also use careful judgement in applying them just like any other tool at your disposal. I think it goes without saying that you should use your ears, but you should also know your sources and what frequency ranges they sit in.

Previous Post

Previous Post

As far as making space in the mix with keys I’ve found the acoustic guitar deserves this type of treatment as well, esp. the ones that blend two pickups- a mic and a piezo. The mic pickup can have low rumble. So I usually high pass it but then you have a song with the first verse primarily guitar and you have to reset the high pass so more of the lows come through.

A low “E” on a 6 string guitar is 80 Hz so you can almost always get away with high-passing a guitar to at least at 80 Hz. That’s probably also why consoles with fixed HPF’s are often fixed at 80 Hz.